Decoding the Operating System of Behaviour: Finding and Fixing Hidden Rules

Part of a series for learning more about the power of Contextual Behavioural Science for understanding and improving group behaviour.

Picture this: You're sitting in yet another meeting that's going nowhere. Sarah keeps interrupting people mid-sentence. Mike agrees with everything the boss says, even when it contradicts what he told you privately the day before. Your work group spends twenty minutes conducting the mandatory check-in round while ignoring the elephant in the room: this project, like most projects the team takes on, is already three weeks behind schedule.

Sound familiar?

What is going on?

It's like everyone is navigating an invisible maze—following pathways that seem logical from inside the maze, but would look completely arbitrary to someone viewing it from above.

It is helpful to imagine these pathways as invisible rules that nobody talks about, nobody wrote down, and probably nobody even realises exist?

These hidden rules are everywhere, quietly shaping how you and those around you behave, what they say (and don't say), and why your best-laid plans keep going sideways. Once you learn to recognise them, you'll never view group dynamics in the same way again.

The Invisible Operating System

Think of these hidden rules like your computer's operating system. Most of the time, you don't see it, but it's controlling everything that happens on your screen.

Every work group, every organisation, every family, indeed every person has these unspoken rules humming away in the background:

"Don't disagree with the boss in public or you'll be labelled difficult"

"If you finish your work early, you'll just get more work piled on"

"Admitting you don't know something makes you look incompetent"

"The person who talks the most gets taken most seriously"

These rules can either drive us toward things we want (such as recognition, safety, or connection) or away from things we fear (like conflict, embarrassment, or failure). Both types are incredibly powerful in shaping behaviour, though we tend to notice the avoidance rules more readily because they create that familiar feeling of being stuck or constrained.

Nobody teaches these rules explicitly. People learn them through experience, picking up subtle cues about what gets rewarded and what gets you in trouble. But once learned, these rules become far more powerful than any policy manual.

Just to be clear: I'm not talking about formal policies written in employee handbooks or official procedures. These are the if-then relationships we've learned through experience, the verbal descriptions we'd give when we observe patterns in our own behaviour. In behavioural science, we call this "rule-governed behaviour," but these aren't actual rules someone created. They're the explanations we'd offer for why we act the way we do if we paused to observe our own behaviour patterns. Some people from a cognitive perspective might call these "mental models," but I see thinking, reasoning, and all motivated action not as representations “inside the mind” but behaviour itself, whether it's inner behaviour (like the verbal descriptions we give ourselves) or outer behaviour (like what others can observe). These verbal descriptions often don't occur to us until something prompts us to look at our own behaviour patterns, which is exactly what this article is designed to help you do.

Where Hidden Rules Come From

Most hidden rules have good reasons for their existence. They are actually the units of our psychological evolution, learned through experience and refined over time. Almost everyone I have ever coached, including myself, has learned a rule like this: "If voices are raised in anger, get the hell out of there, because people will get hurt or relationships will be destroyed." Is it any wonder that conflicts are rarely resolved well in organisations when you consider how almost none of us grew up in households where conflict was managed safely and fairly?

Rules can also emerge rapidly within group cultures. Someone gets burned by speaking up, so they learn to stay quiet. A manager gets blindsided by a project gone wrong, so they start micromanaging. A work team tries consensus decision-making once, and it turns into a disaster, so they default to letting the loudest person decide.

The beauty of rules is that they save us enormous cognitive effort. We don't have to analyse every situation from scratch. Most of our rules are incredibly functional and serve us well. The problem arises when rules become rigid, often because they become attached to our identity ("I'm the kind of person who never gives up") or because we view the world through them without ever checking whether the data continues to support them.

Rules Aren't Bad, Rigid Rules Can Be Unhelpful

Of course, rules are not always unhelpful. Indeed, a major reason we are able to collaborate is because we can provide contingency specifying rules to others that save them lots of time and costly errors. Rules only become unhelpful when they are held rigidly.

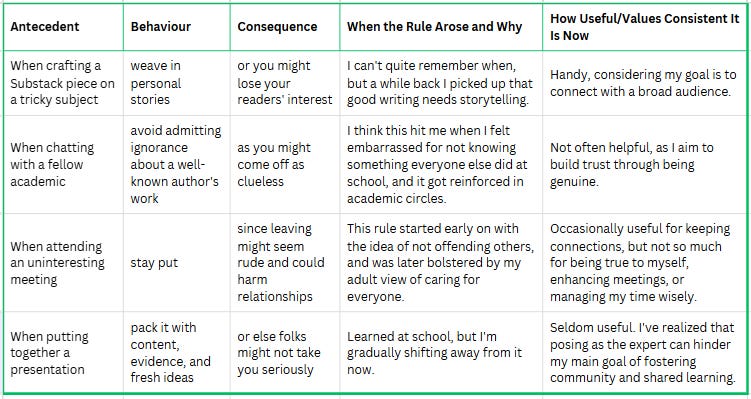

Here are just a few rules I have noticed showing up in myself just this morning (i.e. in the last 3 hours) - some of them are useful for my goals, some not so much:

Can you think of some rules that are guiding your behaviour today? Obviously, there are an infinite number of rules you could construct, most of which we never think about (e.g. "when writing on a computer, use the keyboard to type letters"). I am not asking you to explore the little rules that make up our existence, just the big ones that shape the trajectory of your life, like the last one in the table has for me.

Rigid rules are often even more obvious in groups. For example, I work with many progressive organisations that pride themselves on collaborative decision-making and shared power. They've moved away from traditional hierarchies, created space for every voice, and established processes, such as circles, designed to prevent anyone from dominating.

And their meetings sometimes feel like endurance tests!

Last week I was in a meeting where we struggled to get past the review of previous action points before the meeting was scheduled to complete. Each of the group's participants felt obligated to share their perspective, even when four other people had already said essentially the same thing. Meanwhile, a critical funding deadline was approaching, but the lead author of our most important grant application had quietly made key decisions alone rather than "burden the group" with another lengthy discussion.

The hidden rules at play? A toxic combination that's surprisingly common in well-intentioned groups:

Rule #1: "If we're in a discussion round, everyone must share their view, otherwise you'll be perceived as disinterested or ignorant."

Rule #2: "If you want to get something done, don't bring it to group discussion because it will take too long and generate more disagreement."

Notice what's happening here? In an attempt to avoid the old problem of power concentration, these groups created new issues: decision paralysis on simple matters and stealth decision-making on complex ones.

The Hidden Rule Detective Toolkit

Think of yourself as a behavioral archaeologist. Just as archaeologists uncover ancient civilizations by carefully examining artifacts and patterns, we can uncover the hidden rules governing our groups by examining the behavioral artifacts where the group feels stuck, where the same patterns keep repeating despite everyone's frustration, because that's where you'll find the most powerful hidden rules still operating.

Here are three practical techniques you can use immediately:

1. The Stuckness Spotter

Anywhere you notice behaviour that feels unreasonably rigid, repetitive, or resistant to change, even when circumstances have shifted, you've likely found an outdated rule. Look for:

In yourself:

Patterns that feel automatic or compulsive

Situations where you feel "I have no choice" despite having options

Responses that feel disproportionate to the current situation

Behaviours you continue even when they're not working

In groups:

Phrases like "That's just how we do things here" or "We tried that before and it didn't work"

Meeting patterns that everyone complains about but no one changes

Decision-making processes that feel unnecessarily slow or complicated

Topics that make the energy in the room shift uncomfortably

Work patterns where the same people always take notes, volunteer, or stay silent

The key question: "Is this behaviour serving our current goals, or is it just what we've always done?"

2. The If-Then Detective

Once you've identified potential stuckness, start to formulate a rule based on what people say or do. Listen for statements that follow this pattern: "In these situations [antecedent], if I do X [behaviour], then Y will happen [consequence]."

"In meetings, if I speak up, then I'll be labelled as a bossy woman."

"In meetings, if there is silence, people are bored and they will leave and the meeting will be perceived as a failure."

Sometimes you'll only hear fragments of a rule. When someone says "We must be transparent here," they're stating the context ("here - in this situation") and the required behaviour ("be transparent") but not the consequence. In that situation, you might ask: "What would be the worst thing about not being transparent?" or "What's most important to you about being transparent in this situation?" to uncover their hidden consequence.

These statements reveal the three-part structure of every hidden rule: the trigger (or antecedent) situation, the required behaviour, and the feared or desired consequence. You can remember this as the ABCs of functional analysis.

3. The Safe-to-Fail Experiment

Once you've identified a rule, test it with low-stakes experiments. Let's say you've identified the rule: "In team meetings, if I ask a question that might seem obvious, then people will think I'm not paying attention and I'll lose credibility."

You might test this by deliberately asking one clarifying question in the next meeting. It could be something like: "Just to make sure I understand correctly, when you say 'lets investigate that’, do you mean you will investigate that?"

Then observe what actually happens versus what the rule predicted. Do people really respond with eye-rolls and dismissive comments? Or do others actually seem relieved that someone asked? Often, you'll discover that the feared consequence either doesn't materialise or is far less severe than anticipated. Sometimes you'll even find that breaking the rule produces the opposite outcome. Your "obvious" question helps clarify something that was confusing others, too.

Why This Matters More Than Ever

In our rapidly changing world, yesterday's survival rules can become today's creativity killers. The rule that kept your team safe during the last reorganisation might be preventing them from adapting to new market conditions. The communication style that worked with your old boss might be creating confusion with your new boss.

The teams that thrive are those that can surface these hidden rules, examine whether they're still serving their purpose, and consciously choose to modify or abandon them when they're not.

Your Hidden Rule Challenge

This week, try this experiment:

Notice one aspect of your own behaviour that feels rigid (i.e. insensitive to context or unhelpful)

Ask yourself: What hidden rule might be creating this pattern?

Listen for the if-then structure: In this situation, I must do this to avoid or achieve that consequence

Test your hypothesis: Be bold, try not to follow the rule and see what happens. Is this rule still serving its original purpose?

You might be surprised by what you discover. Just this morning, I noticed an old rule I carry around: "If someone asks you for advice about ProSocial, you should give it for free, because few people in the ProSocial community have funds to pay for coaching." As ProSocial World is currently without funding, we are all having to reevaluate our tacit rules about how we engage with those we serve. Noticing this rule, I decided to test it out. When someone asked me for a free meeting to discuss their latest project, I raised the possibility that they might pay for the session. To my enormous surprise, the person agreed readily, expressing delight that they could do something to help support me and ProSocial World so easily. I suppose I need to review and update this outdated rule.

Once you start seeing these invisible rules in yourselves and in others, you can't unsee them. And that's when you gain the power to change them.

Want to dive deeper? Please let me know your questions or comments below because I would like to write more about this. How can I make this more helpful for you? What questions would you need answered to start regularly seeking to understand relationships through this lens? Would you be interested in getting together for a peer learning group about identifying, articulating and changing these kinds of psychological rules?

Quick Rule Spotter: Think of your most recent frustrating team interaction. Complete this sentence: "In our team, when _____ happens, people tend to ______, because they believe ______." You've just identified a hidden rule worth examining.

In contexts globalization together with growing nationalism and xenophobia, I've found this recurring patterns in two countries I happen to be a naturalized citizen of, on two continents:

"In our team, when a person with a foreign accent makes an unexpected choice, people tend to teach them what the “better or right” choice would be, by national standards, because they believe the "other" party needs to learn how things are done around here."

Whether it is eating with one’s hands rather than with a fork and a knife or choosing to be uncalculating about who's paying for coffee and cake -- at risk of being taken for a fool vulnerable to non-reciprocation - or "go Dutch", the intent may be good or xenophobic.

It may be a kind way of inviting someone into one's culture or it may flop as when the person being "taught" has been a naturalized citizen for 40+ years and the parents the person teaching them did not even know each other at that time because s/he is only 30 yrs. old - begging the question as to who is more the national than the other.

In either case, the rule should be modified to "let it be" or "check on the other’s background first and figure out if they know local practices and are not making an error but are consciously just making a different harmless choice".

Does that work as an example?