On the ACT matrix, "away" does NOT mean "away from values"

The "away" dimension of the ACT matrix tool is often incorrectly equated with "away from values". The matrix comes alive when you understand that the left-hand side is about moving away from pain.

The ACT Matrix is a tool for helping individuals and groups act effectively in the direction of their goals and values by helping them become more aware of what really matters, and more able to handle difficult emotions and thoughts. If you don't know what the ACT Matrix is, start here for an introduction. In this article, I want to dive into one specific question regarding the ACT matrix — what does ‘Away’ really mean.

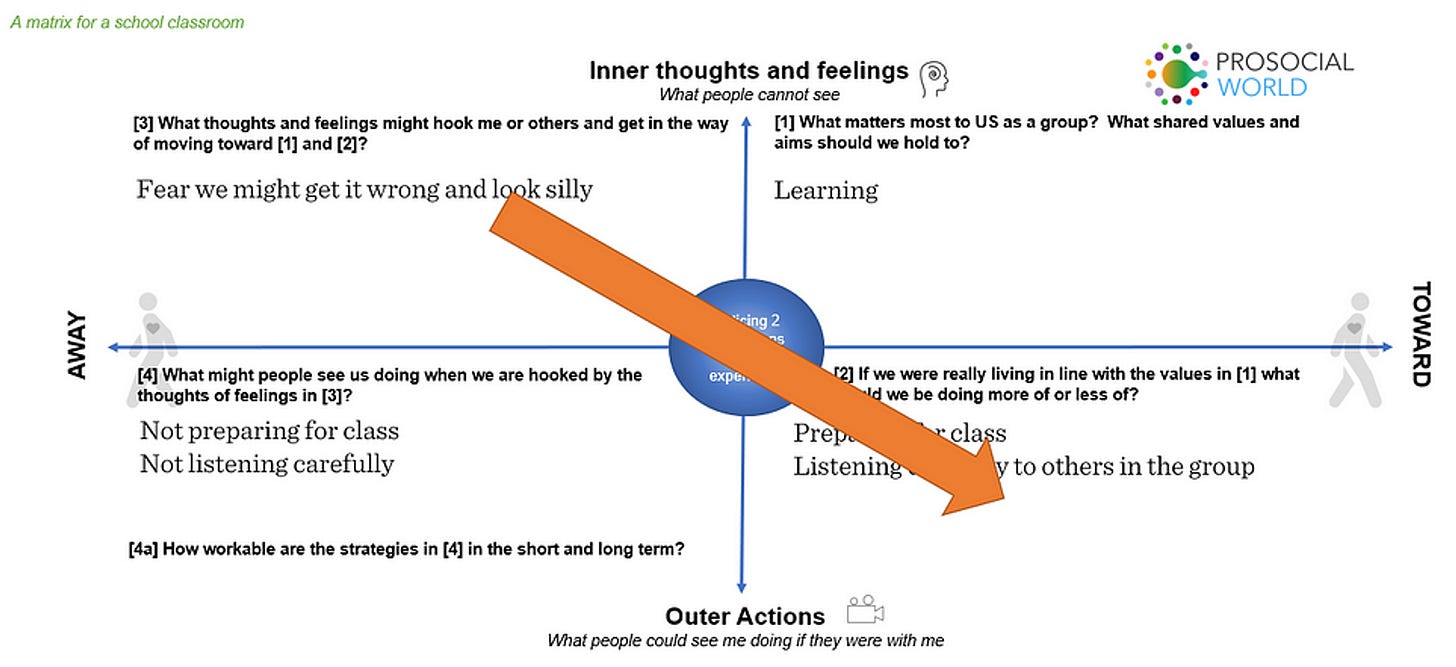

Here is an example of a partially completed collective ACT Matrix. You will see we label the left hand side ‘Away’ and the right hand side ‘Toward’. The points I am going to make in this article apply just as well to a personal/individual ACT matrix.

Figure 1: A typical collective ACT matrix as conducted within the [Prosocial ACT process](https://www.prosocial.world/#:~:text=The Prosocial ARC Process can,and cooperation in different contexts.) with groups.

Many people assume that, since ‘toward’ refers to behaviours that move us toward values and goals, then ‘away’ must refer to behaviours that move us away from values and goals. You can do the ACT matrix this way, and indeed there is a model called “The Choice Point” developed by Joseph Ciarrochi, Ann Bailey and Russ Harris that does exactly that.

But I don't think this is the most helpful way to think about the ‘Away’ dimension in the ACT matrix. Instead, I want to argue, along with Kevin Polk and his colleagues who invented and popularised the ACT Matrix, that ‘Away’ is more usefully interpreted as referring to ‘Away from pain’ rather than ‘Away from values’.

With groups in the Prosocial ARC Process, I usually introduce the right-hand side with a question like “What matters most to us as a group?” This defines ‘toward’ — it is any behaviour that moves us toward those aims, values and needs.

I then usually introduce the left-hand side with a question like “What thoughts and feelings might get in the way of us moving toward what really matters?” Then I use the AWAY-OUTER quadrant to explore behaviours that are designed to move the organism (in this case the group) away from the sources of pain articulated in the AWAY-INNER quadrant.

Let me give you an example. Imagine the following partially (very simplified) collective matrix for a school classroom.

Figure 2: An example ACT matrix if the focus is on ‘away from values’.

The class has identified that learning is their primary purpose and value and they have begun to identify two behaviours that move them ‘toward’ learning; preparing for classes and listening to one another. Of course, in a real collective matrix, there will be many more values and actions on this right-hand side but I wanted to keep the example simple.

Now let's move to the left-hand side. At this point it probably doesnt matter much if you ask ‘What thoughts and feelings take us away from our values?” or “What thoughts and feelings get in the way of us moving toward our values?”. Most groups will treat those questions as synonymous. In this case the main thing getting in the way of students learning might be FEAR of getting it wrong and looking silly. Once again, real collective matrices will map many more AWAY-INNER responses, but I am just using one main example here for simplicity.

So far so good. But the problems start with the next two steps of the matrix. When we move down to the AWAY-OUTER quadrant. Thinking about Away as ‘Away from values’ tends to evoke behaviors that are more or less the mirror image of whatever moves us toward. So instead of ‘preparing’, we get ‘not preparing’ and instead of ‘listening’ we get ‘not listening’. We might not get those exact words, perhaps people will say ‘talking over one another’ instead of ‘not listening’. But the point is that ‘Away’ is defined in opposition to whatever is on the right, not as a means of controlling or avoiding whatever is in the AWAY-INNER quadrant.

So we don't get any new information. All we are getting is what we are doing instead of moving toward our values. We are not learning anything new about patterns of avoidance and control.

Figure 3: Psychological flexibility is the capacity to act in valued directions even in the presence of difficult internal experiences.

Let's look at what might happen if one is careful to define ‘Away’ as ‘Away from pain’ rather than ‘Away from values’.

Now the AWAY-OUTER quadrant is all about what the person does to try to avoid or control their difficult experiences. So now the matrix might look something like this.

Figure 4: An ACT matrix with the emphasis upon ‘Away from pain’ instead of ‘Away from values’.

Notice how the material in the AWAY-OUTER quadrant is a direct response to the the AWAY-INNER quadrant. I try to get over my fear of looking silly by a) copying expert sources rather than stating it in my own words which might be criticised and b) by avoiding doing the work at all until the last minute. When we define ‘Away’ as ‘Away from pain’ we get new information that tends not to be evoked by thinking of it as ‘away from values’.

But there is a much deeper problem with defining ‘away’ as ‘away from values’ and that is that it misses the whole point of doing the matrix in the first place!

The point of the ACT matrix is to help people see where their patterns of short-term avoidance of pain are interfering with the lives they want to live, and in this case the groups they want to create. The point is to build ‘psychological flexibility’, the capacity to act in the direction of what matters (TOWARD-OUTER) even in the presence of difficult thoughts, emotions, imagery, memories and so on (AWAY-INNER).

Figure 5: The point of the ACT matrix is to help people move in the direction of valued actions even in the presence of difficult internal experience.

ACT stands for Acceptance and Commitment Therapy which is an approach that recognises that most psychological difficulties are caused in large part by our ineffective efforts to avoid or control difficult psychological pain. Our society tells us to ‘just get over it’ or ‘think happy thoughts’ or ‘calm down’ but such thought and feeling control simply does not work. To see this, just try this exercise: For the next minute, whatever you do, don’t think of an elephant!’ To know you are not thinking of an elephant, you must by definition think of an elephant. Attempts to control our experience based on getting rid of psychological pain and grasping after psychological pleasure are similarly doomed. And not only are they ineffective, they consume vast amounts of energy that might otherwise be devoted to living the life we want. If you want evidence for this point, take a look at some of the over 400 randomised control trials that have so far been done on ACT.

Benji Schoendorff, one of the main developers of the ACT Matrix, has a lovely question that he asks people when he runs the matrix: “Which side would you prefer to spend the majority of your life on?” Do you want your life to be about a) trying to control and avoid pain, or b) moving toward what really matters, even in the presence of pain? Put like this, it becomes very clear that lives lived more on the right-hand side of the matrix are more vital and engaging than lives lived on the left-hand side.

We can understand more deeply how this works by looking at the processes of reinforcement going on. From an ACT point of view, behaviour is the product of evolutionary processes. Evolution is just variation, selection and retention. In genes, this looks like genetic mutation, adaptive fitness and hereditary processes. In individual and cultural behaviour, it looks like trying out a new behaviour, noticing its consequences, and doing that behaviour more or less frequently in the future depending upon how well the behaviour worked. We approach a doorknob and find it does not open by twisting clockwise, so we turn it anti-clockwise and then jiggle it a bit until the door opens. Next time we approach the same door, we will much more quickly zero in on the anti-clockwise turn + jiggle strategy. In this case, opening the door is positive reinforcement for the turn+jiggle strategy.

From this point of view, everything on the matrix is behaviour. The stuff up the top is PRIVATE behaviour observed only by the person doing the thinking and feeling, while the stuff down the bottom is PUBLIC behaviour that can be seen by others. But both types of behaviour can evolve through variation, selection and retention.

A lot of the typical AWAY-INNER behaviours are patterns of internal responding that we have developed early on in our lives. We might, for example, have presented a new idea and found that we were laughed at by our classmates, or gently scolded by our parents for being silly. Such experiences quite sensibly create FEAR of being ridiculed the next time that one is in a similar situation. What is a young person to do in response to such FEAR? They don't have the perspective-taking ability to see that the ridicule likely has more to do with the other person than with their idea. And, since they lack any objective standard for the goodness of an idea, they are more than likely to simply be influenced by the opinion of the group.

So positive reinforcement is when doing a behaviour results in MORE-OF a desired stimulus or event. Negative reinforcement is when doing something results in LESS-OF an undesired or unpleasant stimulus or event. In both cases, the consequence makes the behaviour more likely in the future. The right-hand side of the matrix is all about processes of positive reinforcement which build vitality and engagement. The left-hand side is all about processes of negative reinforcement, behaviours designed to create LESS OF the aversive difficult experiences listed in the AWAY-INNER quadrant. Whereas the right-hand side is self-expansive, the left-hand side is self-protective.

So, in summary, you are welcome to talk about the matrix as toward and away from values. But if you talk about it as toward values and away from psychological pain it is, in my view, a much richer and more profound tool. The main advantages of using the ‘away from pain’ definition are that :

a) you get a wider range of behaviours, not just mirroring on both sides and, more importantly,

b) it highlights the key psychological process underpinning most suffering — ineffective and draining avoidance of difficult experiences.

If you define away in terms of ‘away from values’, you get to list helpful behaviours on the right and unhelpful behaviours on the left. But you miss why these behaviours are helpful and unhelpful. If you define away as ‘away from psychological pain’, then you get a window into the fundamental processes of positive and negative reinforcement underpinning our suffering — attempts to control or avoid difficult experience that are not only ineffective, but reduce our vitality to pursue a valued life.