Photo by Micah Tindell on Unsplash

Our aim in ProSocial is to create groups and groups of groups that work for everyone. We want our social experience to meet ever more needs of ever more people.

We need to talk about power and its use in society to do that. I did not feel ready to write about power when we were writing the Prosocial book, although I recognised its importance. I now believe that not talking about power, or talking about it casually, is interfering with our mission. Thus, this essay.

Ostrom also did not explicitly focus on the issue of power, at least to the best of my knowledge. Still, the issue of power necessarily runs through her work, particularly in her third core design principle: “Collective Choice Arrangements: Most individuals affected by a resource regime are authorised to participate in making and modifying its rules.” (Ostrom, 2010, p. 253)

This principle is about shared power — what has come to be called ‘power-with’ as opposed to ‘power-over’, terms I will elaborate further below.

When we do not discuss power in groups, we tend to use power unskillfully. And when we use power unskillfully, we decrease the likelihood of creating groups that work for everyone.

Many of the groups in which I participate have moved away from using explicit hierarchical power. But this does not mean that they have moved away from power. Even in groups that seek to embody collective choice arrangements, some people talk more than others or in more authoritarian ways. Some actions and some actors are seen as more legitimate than others, and the majority enforces implicit norms for what is acceptable, resulting in conflict, exclusion or inaction.

An evolutionary perspective on power

From an evolutionary perspective, power behaviour is never good or bad in itself; it is only more or less effective in achieving specific outcomes. In that sense, behaviour cannot be understood outside the context in which it is occurring. Raising one’s voice might be bad in the context of trying to educate a child but good in the context of karaoke. Contexts select behaviours according to our aims.

A core aim of the Prosocial approach is to promulgate this evolutionary perspective on behaviour so that we might move beyond rigid “us and them” patterns of thinking and thereby increase prosociality.

What is power?

Miki Kashtan defines power as “the capacity to mobilise resources to attend to needs” (2014, p. 130). I like this definition of power because it calls out the idea that we don’t use power for its own sake; we use it to satisfy needs, either our own or those of others. Power is pragmatic.

This approach to power allows us to explore the central focus of Prosocial, namely the potential to integrate and balance individual and collective interests. If someone uses their power to benefit only or primarily themselves, we might say they are acting selfishly. If someone uses their power to benefit themselves and others, then we might say they are acting prosocially.

Let’s unpack some of the key ideas in Kashtan’s definition. Power is, first of all, a capacity — it is the potential to achieve specific outcomes. In our individualistic society, some people mistakenly see this capacity as residing in the individual. But power is always relational. We might think of power as having different bases or sources, such as access to information, authorisation by others, expertise or even likeability. However, even the last of these (usually called “referent power”) is a capacity to achieve outcomes based upon a relationship.

Ostrom expressed the relational nature of power in another way, recognising that even personal power was a function of “the value of the opportunity (the range in the outcomes afforded by the situation) times the extent of control.” (Ostrom, 2005, p. 50). Capacity, and therefore power, varies significantly from situation to situation. A ‘powerful’ CEO may be utterly powerless to influence the behaviour of her teenage daughter, for example.

Second, power is the capacity to meet needs. So what are needs? In this way of constructing meanings, based mainly upon the work of Marshall Rosenberg (creator of nonviolent communication — NVC), a need is anything an organism requires to thrive.

Humans, like all living things, need water and nutrients. But humans, with their capacity for language, have also constructed a rich set of psychological needs that can be more or less broadly specified but typically include aspects of experience such as self-determination, belonging, agency, fairness and meaning.

Needs, along with purpose and values, make up one aspect of ‘what matters to me’. i.e. the selection conditions for behaviour. However, whereas constructs like ‘purpose’ and ‘values’ are aspirational and reach for the future, needs are present-focused.

Furthermore, whereas purpose and values tend to vary from person to person, needs are defined within NVC and other needs theories, such as self-determination theory, in terms of universals, aspects of experience that apply to everyone irrespective of culture or circumstance. It is this latter quality that makes them so useful for Prosocial. Talking about needs brings us a sense of shared identity and purpose (CDP1).

Finally, power involves “mobilising resources”. A resource is simply a stock of some sort that somebody can draw upon to get things done. Resources can be anything in our life-world. They can be ‘outside’ ourselves (such as money, tools or relationships) or ‘inside’ ourselves such as skills, knowledge and even more or less useful patterns of responding to stress and challenge.

Whose needs? Power-over and power-with others

I sometimes think of Prosocial as our effort to help people shift from ‘me’ to ‘we’. In behavioral terms, this means moving from making decisions for the good of oneself to making decisions for the good of the group, including oneself. Ostrom’s core design principles are an elegant description of a set of social patterns that tend to decrease the likelihood of purely self-interested behaviour and increase the likelihood of behaviour for the good of the group. And the addition of the psychology of behaviour change creates a set of ‘internal’ conditions that support flexible and functional adoption of these social patterns in helpful rather than rule-bound ways.

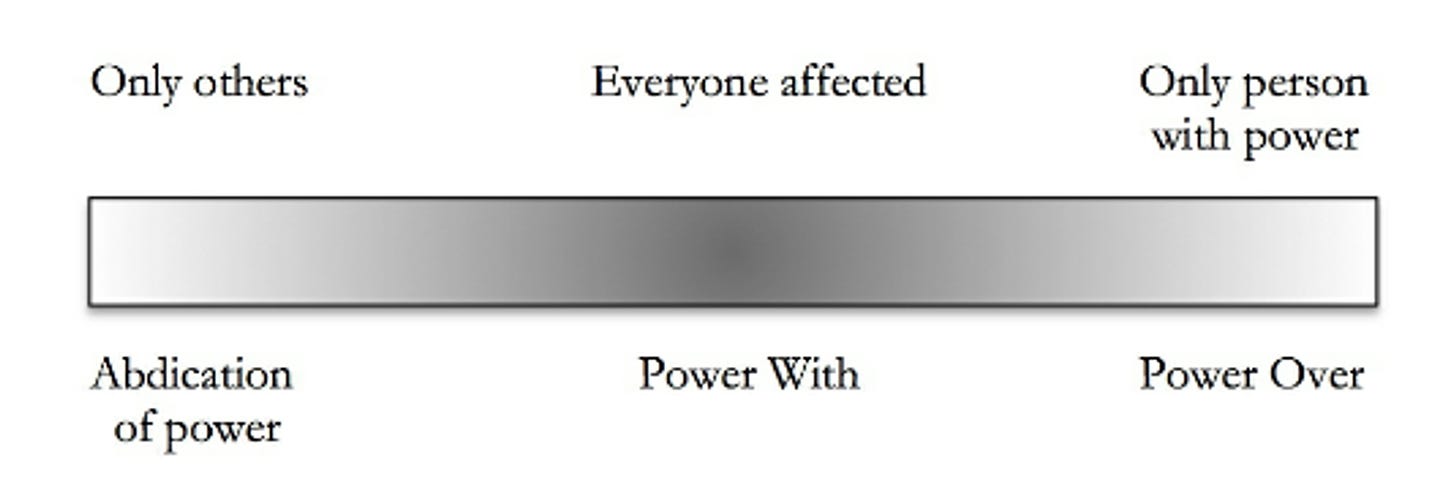

So, if power is the capacity to mobilise resources to attend to needs, then the obvious next question is, ‘whose needs?’ This question gives us a way of understanding different types of power, represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Different forms of power depending upon whose needs are satisfied. (Kashtan, 2015, p. 132)

If we use our power to serve only ourselves, and we are unaffected by the needs of others, then we can call that ‘power-over’ others (Follett, 1940). At the other end of the spectrum, we might give away our power such that others make choices for us, or we make choices based purely on other’s wishes.

Between these two extremes is a form of expression of power where we strive to mobilise resources to attend to the needs not just of ourselves but also of others. We can call this ‘power-with’ others as opposed to ‘power-over’ others.

This is a continuum of choice, and in that sense, it is each person’s responsibility in each moment to decide if they wish to give away their power, use it to meet only their own needs or use it to meet both their own and other’s needs.

Each of us brings a particular relationship to power, born out of our earliest experiences of authority, trauma and social modelling, which tends to influence us throughout our lives. I, for one, grew up with a father who exerted power-over somewhat ineffectually and a mother who strongly modelled and reinforced abdication of power. These experiences left me in my early 40s grappling with the tension between wanting to change the world for the better and deep unease with influencing anybody to do anything at all. Although Prosocial has allowed me to experience deeply nourishing expressions of power, to this day, I still sometimes fail to exert power for the good of the group even when it is warranted, such as naming something that appears ‘off’ to me in a group conversation because I am afraid of disapproval.

So, we bring habits, dispositions and histories of reinforcement and punishment to the expression of power. But, like all behaviour, our expression of power is not purely a matter of personal choice. Different contexts provide more or less support for power over, power with or abdication of power. Groups that rely upon cultures of hierarchy provide strong support for power-over behaviours, while groups that rely more upon collective choice arrangements provide strong support for power-with behaviours. What ends up happening is a function of our personal characteristics and context.

Here, I am reminded of Alexis de Tocqueville, who believed we need to look into the earliest moments of life to understand our behaviour patterns. “We must begin higher up; we must watch the infant in its mother’s arms; we must see the first images which the external world casts upon the dark mirror of his mind; the first occurrences which he witnesses; we must hear the first words which awaken the sleeping powers of thought, and stand by his earliest efforts, if we would understand the prejudices, the habits, and the passions which will rule his life. The entire man is, so to speak, to be seen in the cradle of the child.”

One of the manifestations of this I find interesting is that children of trauma have a propensity to become activists for equality. It seems that the disproportionate power dynamic of a traumatic youth can trigger a need to employ a protective use of power in adulthood.

Power-over is invariably coercive power. If we want to make someone do something for our benefit but not theirs, then we need to rely upon punishing experiences such as fear and changing the contingencies of behaviour so that it is now in their interest to do what we want. Power-over only works when we can deliver consequences for non-compliance that motivate people to do what we want. This typically restricts the range of choices the other can make such that their only remaining option is to do what we want or suffer the consequences. When we are forced to do something, we invariably do it with less creativity and vitality than when we freely choose our actions. Power-with behaviour tends to evoke more creative and robust solutions.

So ‘power-over’ is bad, and ‘power-with’ is good, right?

So far, so good, we have a simple workable understanding of power that seems to line up nicely with whose interests are being served by the behaviour. Obviously, we want more power-with and less power-over in groups! Right? Well … mostly. But it pays not to get too rigid in our thinking.

While preferring power-with approaches is mostly consistent with our aims in Prosocial, there can be some pitfalls with a power-with approach. Kashtan identifies some “myths of power-with” that play out in practice for many groups striving to break out of traditional hierarchical, power-over governance models.

Four Myths of Power-With

Power-with = leaderless and non-hierarchical

The first myth is to see “power-with” as the same as a leaderless group. We are so used to thinking of leadership as power-over that it is sometimes hard to imagine leadership forms that use power-with. But models of leadership such as adaptive leadership (Heifetz and Linsky), servant leadership (Greenleaf) and even transformational leadership (Bass and Avolio) are all potentially expressions of power-with. Conversely, groups without formal leaders can still be hotbeds of power-over behaviour. Whether or not a group has a culture of power-over or power-with has nothing to do with whether it has a formal leader.

Many people equate power-with and having no hierarchical structure in a group. But the reality is that some forms of hierarchy can be enormously helpful in organising collective action. And not all hierarchies involve power-over. Consider, for example, the hierarchical structure of a Sociocratic organisation where ‘circles’ are dedicated to working on particular outcomes at different levels of the system. A community, for example, might have a ‘general circle’ focused on the broadest, long-term purpose of the community and a local circle devoted to maintaining the chicken yard. This is a hierarchy of information rather than a hierarchy of power-over. Organising by scope and time-span of decision making, group members can make decisions in a focused way without having to draw upon everybody, all of the time.

In a sense, the ProSocial core design principles ensure that the benefits of hierarchy are retained without power-over behaviour. Indeed, they are explicitly designed to create agreements and processes that limit the possibility of exerting power-over. CDP1 helps establish shared purpose so that decisions can be made for the good of the whole, not just individuals, CDP3 explicitly invokes collective choice arrangements to minimise the chance of choices being made out of self-interest and CDPs 4 and 5 help to create a culture of transparency and feedback.

Power-with = not-excluding anybody from the group

Another mind trap is to think that a group that embodies power-with must necessarily be open and inclusive of all. Kashtan highlights how attempting to include everyone can involve including someone whose behaviour actually excludes others. Whether as a result of personal characteristics (e.g. trauma, past patterns of social modelling and reinforcement, or just plain old lack of skill) or divergent beliefs about the purpose of the group, some people act in ways that are unhelpful for the group. And when this happens, it makes others leave, including those who were acting for the good of the group.

This is why in Prosocial, Ostrom’s principle of graded sanctions for unhelpful behaviours is so critical. Trust and cooperation go down not up when a group cannot exclude someone who is acting against the broader interests and purposes of the group (e.g. Kerr et al., 2009).

In my own life, I am seeing this unfold in my local Extinction Rebellion (XR) group. XR groups rely upon highly distributed forms of leadership and, being voluntary, this means that few people are willing to incur the emotional, reputational and time costs associated with trying to exclude someone from the group. Combining this with an ethos of inclusion of many points of view, and the conditions are right for disaster. In this case, a small minority of members have been actively dismissive and hostile towards the core XR principle of nonviolence, arguing that violent actions such as abusing the police or damaging property are more likely to attract attention than nonviolent resistance. In essence, this is a major difference of opinion regarding the purpose of the group. As local organisers spend many hours and a great deal of emotional energy trying to persuade this minority to adopt non-violence, others are leaving the group in dissatisfaction as the central principle of nonviolence that caused them to join the group is openly flaunted in public demonstrations.

Excluding people might feel like ‘power-over’. If we were to consult with the minority they would not freely choose to leave the group. But what if their aims directly contradict the aims of others in the group? This is one place where the simple ‘power-over = bad’ equation does not hold.

Trying to include everyone is a form of rigidity that is actually not helpful for the health of the group. It is like saying that we will welcome all cells into a body, even cancerous ones. The ethic of the principles is that we welcome people and actions that are supportive of the health of the whole system.

Marshall Rosenberg’s notion of ‘protective use of force’ is helpful here. We would have no hesitation to drag a child out of the path of an oncoming car. Similarly, we may need to apply force to protect the broader interests of the collective if, after extensive consultation, a minority insists on pursuing different aims to those agreed upon by the rest of the group.

So force can sometimes be applied for the good of others or for the good of the group as a whole. This is always a fraught process but it is an illustration of why clarity of shared purposes (CDP1) is so critical. The only criterion we can have for applying power-over and excluding someone is whether their behaviour supports or works against the group’s purpose.

Power-with = involving everybody in decisions

In Figure 1 above, power-with is equated with involving ‘everybody affected’ by the decision. But in practice, seeking to involve everyone in decision making is likely to work against the interests of the group for a variety of reasons:

Not everybody can be present all the time for decision making. Sometimes a decision has to be made in a timely fashion, irrespective of whether everybody affected by the decision is present.

Sometimes people affected by the decision can express their needs but they lack the expertise to actually make the decision.

Sometimes people will express an opinion if asked but really would not have cared if the decision was made without their input provided the decision is made with due process by those with sufficient expertise.

Sometimes people would rather not experience the costs of having to make a decision. I remember working in a call centre where group members hated the fact that they were called upon to have input to decisions.

One key distinction that is helpful here is the distinction between operational and governance decisions. Operational decisions can easily be delegated to those with responsibility for a domain, but governance decisions (decisions that relate to how the group makes decisions) are long-term and tend to affect more people and so usually require broader input.

A variety of decision-making processes have evolved to embody power-with in ways that are reasonably efficient and practical in groups. One such approach is the Advice Process. Another is the process of a) establishing objective criteria for a good decision, b) encouraging proposals for action and then c) making decisions by consent as embodied in Sociocracy and Miki Kashtan’s Convergent Facilitation approaches.

The common feature of all of these approaches is that they strongly support the decision-maker(s) to take everybody’s needs into account when making the decision. Our ability to take the perspective of others means that not everybody has to actually have input to a decision, provided that others are sufficiently skilled and motivated to anticipate and consider their needs.

This is why citizen’s councils, assemblies and juries can work as a form of representative democracy. Provided you have a representative group that has the skills and interests to come up with a solution that works for all, you don’t need to consult every citizen over every decision. And you can greatly support this process by building in learning and feedback loops that encourage review of decisions, thereby further ensuring it is in the interests of decision-makers to act for the collective good. Certainly, such approaches would be a vast improvement on what we call ‘representative democracy’ today where politicians are held to account just once every three years and the rest of the time largely act in their own interests.

Power-with = prioritising connection over task achievement

For many years in my leadership classes, I have pointed out that good leaders pay attention to both the task and relational aspects of relationships. Excessive attention to tasks creates groups that are mechanistic and uncaring. Excessive attention to relations creates groups that are inefficient and ineffective.

Many groups seeking to implement power-with approaches tend to err too far in the direction of the relational aspects at the expense of the task-focused aspects and this can work against the good of the group.

Kashtan provides the common example of a group engaged in a discussion about an issue. At some point, someone becomes upset and the facilitator-leader turns all their attention to the person to try to resolve their upset. As this drags on, others in the group begin to get upset because the group is no longer making progress towards their task. Soon the group descends into unhelpful conflict.

This dynamic can be easily avoided by having clarity about the potential tension between maintaining connectivity between people and maintaining progress on tasks. Sometimes the group may need to choose to suspend task progress in the service of healing connectivity. Other times it may need to suspend individual healing, or at least take that offline with the person leaving the room with someone, in order to support the good of the group in continuing to move forward on its task.

Power and Culture

Up to this point, we have focused on power from the perspective of the individual — “Am I making choices for the good of the group or primarily for myself?” Let us shift our lens and consider some examples of power-over and power-with cultures.

Schooling and parenting often (although certainly not always) begins from the perspective of acculturating the child to fit into the needs of authority figures rather than engaging in a conversation that includes both the child’s needs and perspectives and the needs of their carers and teachers.

And the fact that only a small minority of us are fully engaged at work speaks volumes to the extent to which traditional workplaces privilege the needs of those in authority over those who do the work. This latter trend has been accelerating in recent decades as the processes of capitalism have rendered most of us into mere individual consumers, thereby vastly compressing our needs for freedom, connection, nature and free time, and relationships become transactions where the minimal act of exchange substitutes for any deeper form of relationship.

The best examples of power-with cultures that I have seen tend to be those of indigenous peoples where resources are seen as belonging to the whole, not individuals, and where there is a sense of stewardship of those resources not just for the group but also for future generations and the broader ecology. In many indigenous cultures, traditions include consensus processes where many people get to speak and all are involved in decision making. Such processes are the very embodiment of power-with provided that they account for the needs of all affected.

A culture can be understood as a kind of story that provides meaning about who we are, how we should do things and what we are hoping to achieve. Since the early 1980s the power-over narrative has been strengthened by an emphasis upon individual achievement, ownership and consumption that has lionised self-interest and eclipsed free time and care-work while rendering the public good as the sole responsibility of governments. At the same time, there has been a systematic effort to reduce the size of governments so as to encourage supposedly more efficient private interests. When winning at life is defined as acquiring as many resources and power as possible for oneself, even at the cost of significant portions of the population, even platforms like Facebook, Airbnb and Uber which their owners portray as enabling sharing, ultimately end up entrenching power-over and eroding genuine power-with.

A power-with culture starts with a different worldview, more akin to that of the commons. Where resources are seen as shared and the responsibility of people is to steward those resources not just for their own benefit but for the benefit of others. A key aspect of this worldview is a sense of abundance. Power-over cultures are driven by the fears associated with scarcity mindsets: “Only some needs can be met and if you meet your needs I will be unable to meet mine.” Put another way, “if I share power with you, you will meet your needs and not mine (after all, that is what I would have done!)”. But this scarcity worldview has been artificially created and inflated by the win-lose dynamics of capitalism. A key part of shifting culture is to recognise experientially that one’s needs are finite and shared such that it is possible to create a society that truly works for all.

So how can we build power-with cultures?

If we start with an aim of meeting as many needs as possible in a group, there are good reasons for attending to the way that power is expressed within a group. Finding forms of power that balance the good of the group with the good of the individual is a global challenge in a time when most of us have been enculturated by models of parenting, schooling and organisational life that have relied heavily upon power-over. How then can we create a culture of power-with rather than power-over in a group?

In this section, I want to use the Prosocial core design principles to articulate one approach to building cultures within and between groups that embody power-with rather than power-over. To date, the principles have been seen as a kind of checklist of necessary but not sufficient conditions for enhancing within and between-group cooperation. In this section, I want to treat the principles more like a sequence.

We think that the Prosocial model has the potential to help groups shift to more power-with cultures. But, by definition, this cannot involve the application of Prosocial as a kind of prescription for all groups. To use Prosocial in that way would be to exert power-over — telling rather than listening, and privileging the needs of the leader/facilitator over the needs of the immediate context. Applying Prosocial not only requires considerable sensitivity skills of awareness and listening but also a kind of discernment regarding the right course of action based on core principles: “Does this collective action serve our purposes in a way that respects the multiple levels of interests (aims, values and needs) including the group, its members and possibly even the broader system to which the group belongs?”

Imagine, for the purposes of argument, that we are building a new group and we want that group to embody power-with, not power-over. Upon what should we focus first?

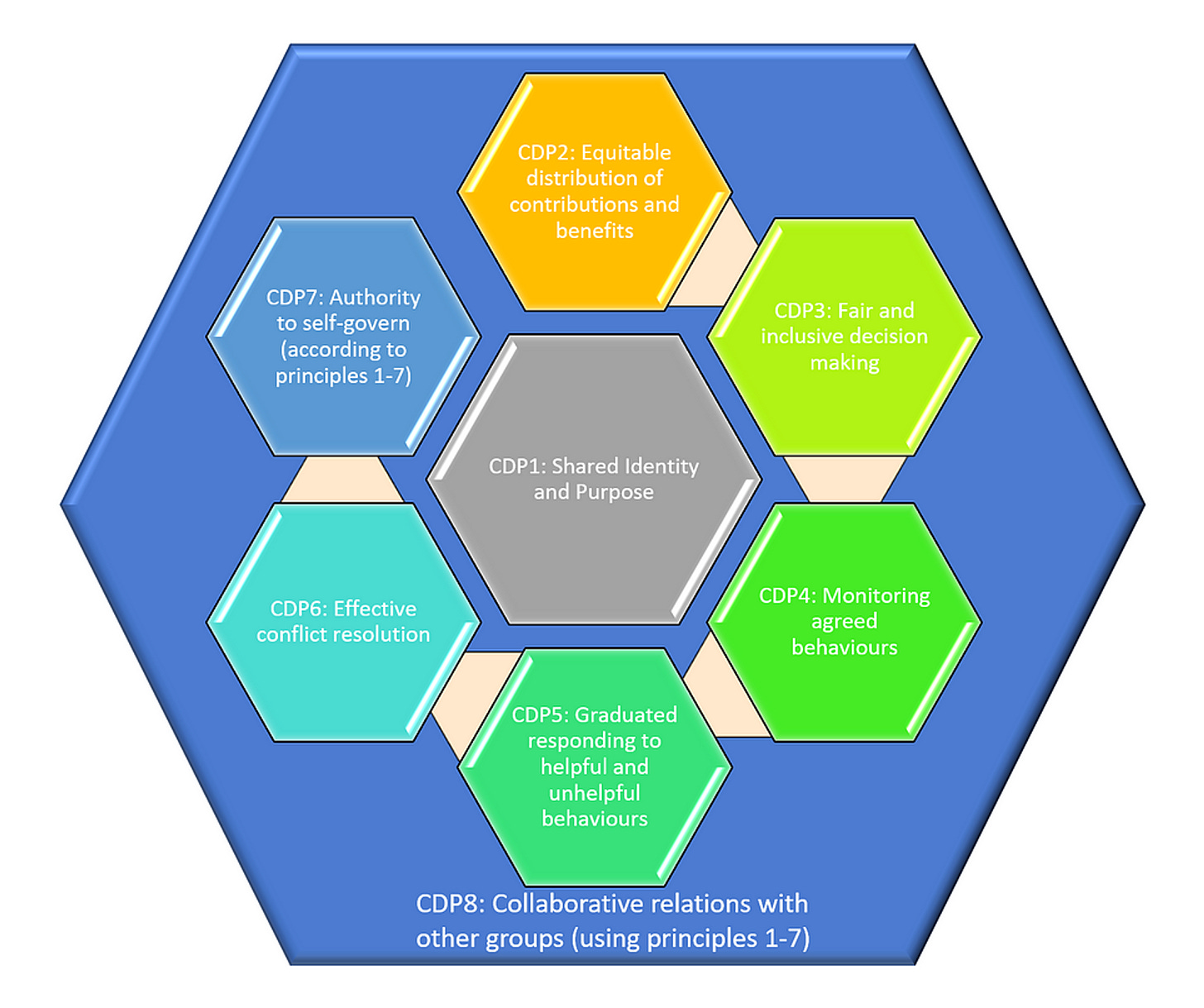

I think that we can learn a lot from the ordering of the eight Prosocial core design principles:

Figure 2: The 8 Prosocial Core Design Principles adapted from the work of Elinor Ostrom (1990): CDP1 Shared identity and purpose, CDP2 Equitable distribution of contributions and benefits, CDP3 Fair and inclusive decision making, CDP4 Noticing agreed behaviours, CDP5 Graduated responding to helpful and unhelpful behaviours, CDP6 Effective conflict resolution, CDP7 Authority to self govern (according to principles 1–6) and CDP8 Colleborative relations with other groups (using principles 1–7).

I want to suggest that our first order of business should be CDP1 and CDP2. These two principles, introduced in a way that embodies psychological flexibility, establish the foundations upon which all other activity will be built:

From CDP1, a clear sense of shared purpose, which necessarily involves taking account of how the group will both take care of its parts (individual interests) but also the role it will play in its broader ecology (why the group exists), and a story of shared identity and belonging that values the members of the group.

And from CDP2, a valuing of the needs of everyone within the group not just those of a few.

I want to elaborate a little on this last point. In my experience of working with groups on CDP2 (Equitable distribution of costs and benefits) I have found that it is usually less helpful to ask “what would be a fair distribution of resources here?” and more helpful to ask “how can we create a situation where everybody’s needs are met?” The former question evokes frames of comparison and human beings exhibit cognitive biases such as motivated reasoning and egocentric biases that mean such a question is likely to increase competition rather than collaboration. By contrast, the latter question, supported by skilled facilitation, evokes shared needs, perspective taking and care for others.

Essentially I am arguing that there is value in interpreting CDP2 as a call to create a ‘win-win’ culture where everybody’s needs are valued. Of course, we can easily justify this choice from science. Groups where everyone’s needs are considered are more stable, satisfying and productive (see, for e.g., Hayes, Atkins and Wilson, 2021). But do we really need science? Who amongst us really wants to live in a world where others suffer to meet our needs?

So CDP1 and CDP2 taken together establish what the group is about (purposes or aims), who belongs (and who doesn’t) and they establish the central idea that everyone’s needs matter. This has built the skeleton of the group, the shape it will take and the framework upon which all else will hang.

At the risk of over-extending the metaphor, the next order of business is to build a nervous system for the group — it must have a way of deciding how to act in the world — CDP3. Groups without a way of deciding cannot act intentionally toward their purpose.

If we want to build a culture of power-with, then making use of one of the decision models I have already mentioned such as the advice process or one of the many varieties of consent-based decision making will ensure that those who are affected by decision making are appropriately and efficiently involved in the making of decisions. I said earlier that I did not want to be prescriptive and certainly I anticipate that there might be contexts where such models may be too time-consuming (intense emergency action for example) but I think these are the exceptions and, generally speaking, we could make a profound difference in our society if we were to begin teaching consent-based decision making at an early age as some schools are already doing.

Next, I would turn attention to the cluster of inwardly focused design principles CDP4, CDP5 and CDP6. All groups need ways of seeing what other parts of the group are doing, and ways of responding to support helpful behaviours and discourage unhelpful behaviours. What is more, whenever people are encouraged to act authentically, there will inevitably be differences in strategies for meeting needs that need to be resolved. If I had to choose an order within these three principles, I would probably recommend the following:

CDP6 — work out what to do if decisions lead to conflict rather than alignment

CDP4 — observe how it is working

CDP5 — develop celebration and course correction responses for encouraging and discouraging behaviour for the good of the group

Then I would turn my attention outwards to see if the group has enough authority to self-govern (CDP7) these earlier processes (CDP1–6). I find it helpful to talk about CDP7 in the negative, is there interference with the group’s capacity to act in line with purpose, make decisions and self-regulate its members’ behaviour? If there is significant interference, how can the group demonstrate to its context that it would be more effective as a self-regulating unit?

Finally, CDP8 provides us with an opportunity to explore the quality of relationships with stakeholders. Can a power-with culture be built at a more systemic level by ensuring greater alignment of purpose, greater equity, shared decision making, shared measurement of key outcomes and processes for noticing and responding to other groups? This is not just about the group being well looked after by the context, it is also the group making a positive contribution to the good of the whole.

Of course, the role of the group in its context (CDP7 and CDP8) might be where the group starts. I repeat that I am not advocating a one-size-fits-all approach. You should start where the energy is. But if you have a blank slate, and you are wondering how to prioritise effort, this sequence appears to me to be logical given the needs of a group.

Power properly understood

Power is like electricity, it can be used to shock people or it can be used to build and run life-saving ventilators. It can destroy or it can create. If we see power as a bad thing, then those of us who long for a more cooperative world are likely to diminish our influence in the world for fear of inappropriately exerting power-over. But armed with a more nuanced sense of power-with, we can better give voice and action to the more beautiful world that our hearts know is possible.

In the words of Dr Martin Luther King:

Power, properly understood, is the ability to achieve purpose. It is the strength required to bring about social, political, or economic changes. In this sense power is not only desirable but necessary in order to implement the demands of love and justice. One of the greatest problems of history is that the concepts of love and power are usually contrasted as polar opposites. Love is identified with a resignation of power and power with a denial of love. What is needed is a realisation that power without love is reckless and abusive and that love without power is sentimental and anemic. Power at its best is love implementing the demands of justice. Justice at its best is love correcting everything that stands against love.

(Carson, 1998, pp. 324–325)

Acknowledgement

This work was largely born in response to Miki Kashtan’s (Kashtan, 2014) book “Reweaving our Human Fabric”. Marshall Rosenberg’s Nonviolent Communication (NVC) has had a profound influence on my life and I feel a deep sense of gratitude to Miki Kashtan for helping me to situate NVC in the broader context of evolving a culture that aspires to meet more needs of more people and the planet.

References

Carson, C. (1998). The Autobiography of Martin Luther King (Kindle Edition ed.). New York: Grand Central Publishing.

Follett, M. P. (Ed.) (1940). Dynamic Administration: The Collected Papers of Mary Parker Follett. London: Pitman Publishing.

Hayes, S. C., Atkins, P.W.B. & Wilson, D.S. (2021). Prosocial: Using an evolutionary approach to modify cooperation in small groups. Applied behavior science in organisations: Consilience of historical and emerging trends in organisational behavior management. R. Houmanfar, M. Fryling and M. Alavosius. New York, Springer.

Kashtan, M. (2014). Reweaving our Human Fabric: Working together to create a nonviolent future Oakland, CA: Fearless Heart Publications.

Kerr, N. L., Rumble, A. C., Park, E. S., Ouwerkerk, J. W., Parks, C. D., Gallucci, M., & van Lange, P. A. M. (2009). “How many bad apples does it take to spoil the whole barrel?”: Social exclusion and toleration for bad apples. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(4), 603–613.

Ostrom, E. (2005). Understanding institutional diversity. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Ostrom, E. (2010). Beyond Markets and States: Polycentric Governance of Complex Economic Systems. The American Economic Review, 100(3), 641–672. doi:10.2307/27871226